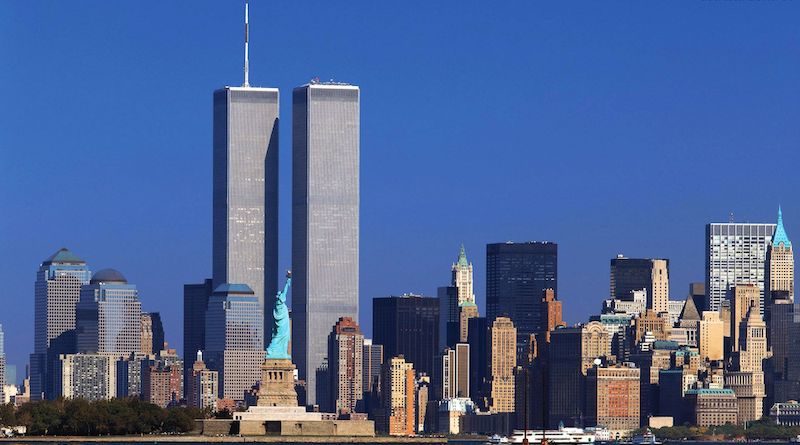

“The memories will be there forever” – the 20th anniversary of 9/11

Nicky Mason

Kenny Cosgrove

Steve Jary

Today marks the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the USA. Those of us who were alive at the time will never forget what we were doing on that day.

The Branch is remembering the occasion by talking to Nicky Mason, Group Supervisor, Oceanic Control and Kenny Cosgrove, ATCO 2, who both worked in Oceanic Control (Prestwick Centre) on the day in question. We also speak to Steve Jary, Prospect National Secretary who was on the last flight to land in London City on 9/11. These are their memories.

September 11th 2001: that morning…

Nicky: I started at 10am and it was an ordinary morning shift and heavy westbound over the Ocean.

Kenny: I remember it like it was yesterday. I was on a 2pm start (9am NYC time) as a late-stage trainee, and in the restroom right around the time the first plane hit the Twin Towers – I thought it was a light aircraft. While watching, a second one banked round towards the second tower and I realised there was something more to it and so I told the Ops room.

Nicky: At about 2.20pm news came from the restroom about the attacks, followed shortly after by a call from Gander to say that US airspace was closed.

Kenny: Most people thought it wouldn’t have any effect as most of the Oceanic traffic for the day was mid-Ocean; there might be delays to New York flights. After plugging in to train on the sector, an aircraft turned-back suddenly and of its own accord. Then others started to do the same…

The impact on the Ocean…

Nicky: Very quickly, there were multiple aircraft requesting to turn around and come back to Europe. For maybe five minutes, there was a sense of ‘what are we going to do?’ Some aircraft continued westbound into Canadian airspace, some turned back from 40 West, deep in Gander’s airspace, and some diverted into Reykjavik which quickly filled up. The Ocean had four sectors open, quickly becoming eight. Some controllers living nearby and watching the news unfold came into work.

Kenny: The problem was that as everything had gone out earlier in the day, it was all now on its way back.

Nicky: Everyone got stuck in. Every single person that was there was made useful. Sectors were divided at individual flight levels as much as possible. I had 22 turn-backs which for one session is a very high workload. You would normally expect 2-3 per year. I worked on the premise of ‘last in, first out’ – so the aircraft that was last to join the North Atlantic (NAT) tracks was the first to be turned round. This way, they would always be separated from each other as they weren’t seen in the non-radar Ocean environment.

Kenny: People in the offices who were valid plugged-in and no one left the Ops room the whole day. I became an ‘estimate passer’ to Shannon, making calls to Gander etc. I was instructed to run up to the canteen to get supplies for everyone, and I did run as I was needed back to pass estimates. Most people worked extended periods of time. It was professional. The operational staff were focussed and developed a system to handle the turn-backs after a couple of hours.

What was it about the environment that helped with the circumstances?

Kenny: The training prepared you very well for turn-backs themselves because you always got asked by instructors, ‘what would you do now if an aircraft turned back?’

Nicky: There was no training for a mass turn-back scenario though.

Kenny: I always anticipated that something major might happen, just as other events have happened in the past, yet the scale was obviously unprecedented.

Nicky: Oceanic separations at the time were quite large, allowing scope to do things; it made it easier to turn aircraft around. The challenge was getting a process in place quickly to be able to deal with something of that scale.

The aftermath and the days that followed…

Nicky: I finished my shift, designed the NAT tracks for September 10th, and called New York Center that night. The guy I was speaking to had lost friends and relatives which brought it all home.

Kenny: We were given support afterwards. CISM was in its early days and was offered. The Bank Sup had a chat with everyone and because it was quiet, everyone was able to talk amongst themselves. I didn’t validate for a while because there was no traffic. On my next night shift, there were only five aircraft in the Ocean.

Nicky: In Prestwick, we were satisfied we had done our bit. Every aircraft we worked was accounted for. There was a lot of opportunity to talk about it amongst ourselves for days afterwards as it was quiet. The support was from our peers.

Has the impact of Covid-19 brought back memories?

Nicky: Covid has been completely different. After 9/11, traffic died off for not that long. This has been a more prolonged hit.

Kenny: There is a lot of chat amongst those who were on that day; we regularly talk about it. Even on a busy day today (pre-Covid), “there’s nothing like 9/11". But the traffic will build back up again, it always does.

What is the legacy of that day?

Kenny: The team that was on was cemented as a group. A lot of comradery resulted as we’d all been through something together.

Nicky: The teamwork part of it was outstanding, alongside Shannon. Shannon was accepting traffic that they had no details of at short notice. The memories will be there forever. I feel like there’s nothing the job can throw at me that I can’t cope with.

And on the last flight into London City on 9/11…

Steve: While everyone can probably remember where they were when it happened, my 9/11 experience made it particularly salient. Working as a negotiator with IPMS (which became Prospect just two months later), I had a meeting in Edinburgh. At the airport mid-afternoon for the 1600 back to London City Airport, my mobile rang. It was my partner: “you won’t believe what is happening in New York…” I replied “Thanks. You do know I’m heading for a flight into the UK equivalent of downtown Manhattan, don’t you?!”

The scene in the departure lounge was surreal. The departures board streamed ‘Delayed’. All the TVs were off. Passengers were getting calls from friends and family. A row broke out, with everyone demanding that the airport put the TVs back on. The managers said they didn’t want to alarm people! Eventually, the demand for information won.

Many flights were cancelled. The news went round that all trains to London were already booked-out. Eventually, ScotAir JY765 boarded. The pilot came over the tannoy: “We’re a little delayed while we take on extra fuel so that we can return to Edinburgh if London City is closed. Anybody who wishes to get off can do so and we will understand why; it’s your choice.” About half of the 16 or so passengers disembarked.

The flight was uneventful, but everyone was looking anxiously out of the windows on the approach into City – checking that Canary Wharf was still intact. We were told we were the last flight into the airport before it closed.

In solidarity

Prospect ATCOs’ Branch

September 11th 2021